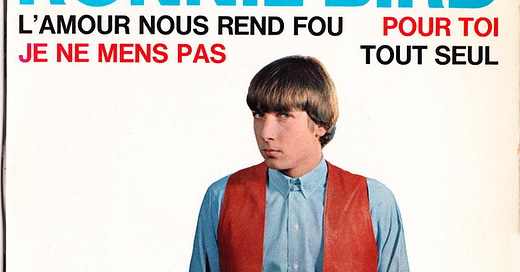

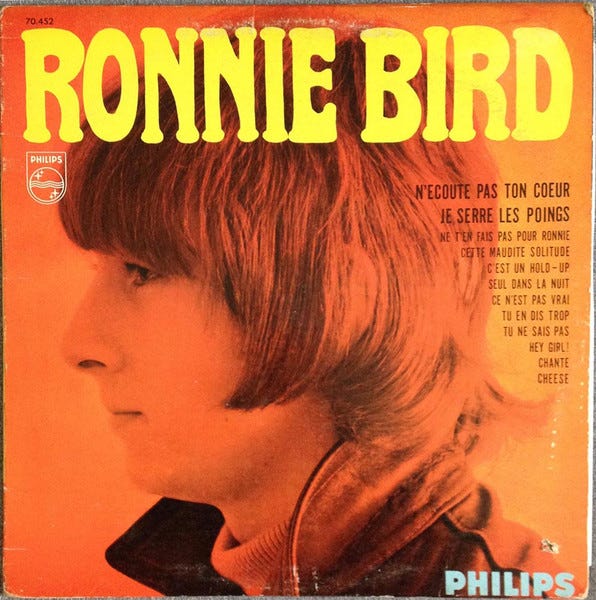

For decades the French were considered to be inferior purveyors of rock ‘n’ roll… by English speaking listeners and critics. When it came to applying the language of Molière to rockin’ rhythms, French singers and musicians were basically seen as wipeouts. Growing up in the predominately French-speaking city of Montreal, I didn’t often encounter that kind of prejudice, but I admit to having been very ignorant in my youth of the rock and pop France produced, even in my fave musical decade, the Sixties. I suppose it didn’t help that I mainly listened to English radio stations which never played oldies by French acts. It was only by the time I hit my mid-twenties that it finally dawned on me that there existed a treasure trove of ‘60s rock and pop from France and that was when I saw Ronnie Bird on the cover of Jukebox, a French record collector magazine I bought. I didn’t have the foggiest notion of who this fellow was.

The scorn Anglophones had for Gallic rock was somewhat understandable given the subpar efforts at emulating American r’n’r to come out of France in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s. The first French rock ‘n’ roll idol was Johnny Hallyday who was his country’s answer to Elvis. Hallyday was okay as a watered-down version of the real thing and probably recorded his best material in the late Sixties. Other early French rockers included Eddy Mitchell and Dick Rivers whose appeal over American acts rested on their being homegrown talents who sung in French. In the early ‘60s, France saw the emergence of instrumental combos largely influenced by British groups like the Shadows as well as young female vocalists like Sheila releasing frothy forgettable pop. The twist also hit the French hard, and a good number of records cashing in on that major dance fad came out. “Yé-yé” was the umbrella term used to call this variety of styles.

What helped to ultimately make French pop and rock more than just a pleasant diversion was the major impact that the Brits had on France’s songwriters, singers, musicians, arrangers and producers, starting in 1964. Nowadays, Serge Gainsbourg, Jacques Dutronc, and Michel Polnareff are lauded by pop lovers and record collectors as significant figures whose brilliant music could equal that of Anglo-American acts. But one name that doesn’t crop of as often when discussing the makers of great Gallic ‘60s pop/rock is Ronnie Bird, a man who I believe deserves to be in the company of the French musical legends mentioned above.

Although that copy of Jukebox magazine succeeded in informing me about Ronnie Bird and his discography, it took a couple more years for me to finally give him a listen. In the meantime, I got into the superb 1966 debut album by the fantastic Jacques Dutronc. That LP consisted of acerbic and ironic social commentary wed to a British r'n'b-derived garage rock beat. Dutronc’s songs reflected the strong influence of Bob Dylan. So did the singles I discovered by Antoine whom I’ll discuss in greater length below. When it came to Ronnie Bird, I eventually scored a mint copy of his first long player at a Montreal flea market. It only cost me a buck, perhaps the best dollar I ever spent on an album. It was a mixture of originals and covers that demonstrated that Bird could easily and convincingly handle both British rhythm’ ‘n’ blues and American garage.

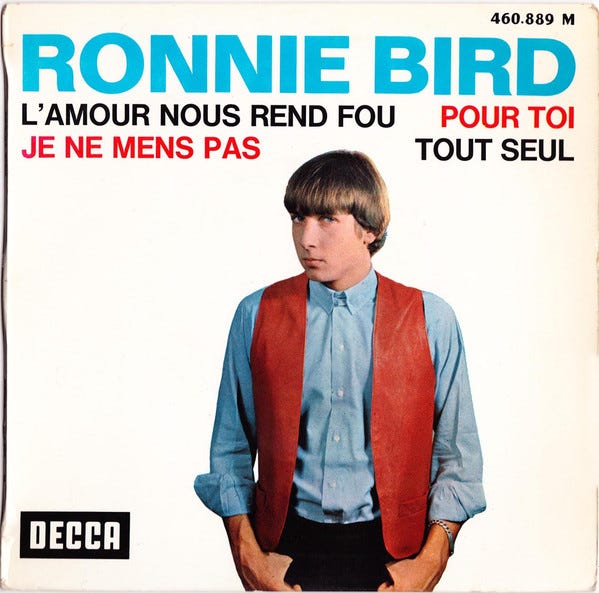

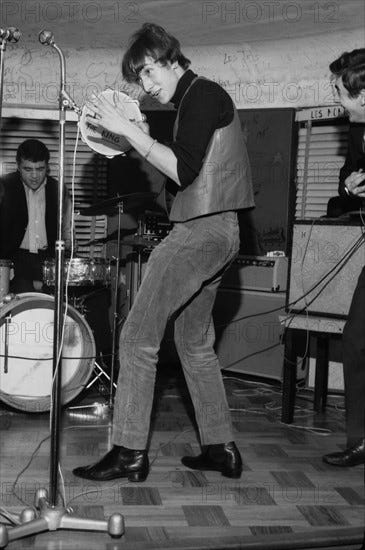

In fact, Ronnie Bird prefigured Dutronc and Antoine when it came to modernizing “le pop français” in 1965. He was the first French singer to capture the spirit of the Rolling Stones’ surly and rebellious attitude. Bird even looked like a member of the Stones, sporting a perfectly coiffed Brian Jones-like moptop and mod clothes that seemed to come directly from Carnaby Street boutiques. He was born Ronald Méhu in 1946 and hailed from the suburbs of Paris. The sounds of ‘50s rock ‘n’ roll pioneers like Elvis, Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, and Little Richard had a profound impact on young Ronald who picked up English thanks to a number of sojourns in the UK. He initially thought of becoming a photographer or a film director, but then decided to devote himself to music, adopting the stage name of Ronnie Bird. When he was seventeen, he formed his first group, les Blazers. A year later, in 1964, he dropped out of school and fronted another band called les Rebelles. Bird successfully auditioned for Decca Records and, also in ’64, released his debut 7”, an EP which included “Adieu à un ami”, a cover of “Tribute to Buddy Holly” originally cut by English singer Mike Berry. Ronnie’s record was produced by the Black American expat, guitarist extraordinaire Mickey Baker, who had played with Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, Ruth Brown, and Little Willie John, among other r’n’b legends.

“Adieu à un ami” was a pretty good start for Bird and was followed at the end of the year by his second EP containing the outstanding track, “Tu ferais mieux de filer”. This was a rough-edged r’n’b original, written by Ronnie, Mickey Baker, and Claude Righi, and an indication of better recordings to come.

Baker would continue to work with Bird for a while as guitarist on his sessions and co-writer, and Righi would also be involved in composing or translating future songs for the singer. In the meantime, Ronnie continued to make a name for himself, energetically performing with a revolving door of backup musicians, in the hottest Parisian clubs catering to rock ‘n’ roll hungry youth: le Golf Drouot, la Locomotive, and le Bus Palladium. Along with the material he had recorded, he and his group would tear through their versions of “Carol”, “Route 66”, and “Walking the Dog”, all of which had found a place on the Rolling Stones’ debut LP.

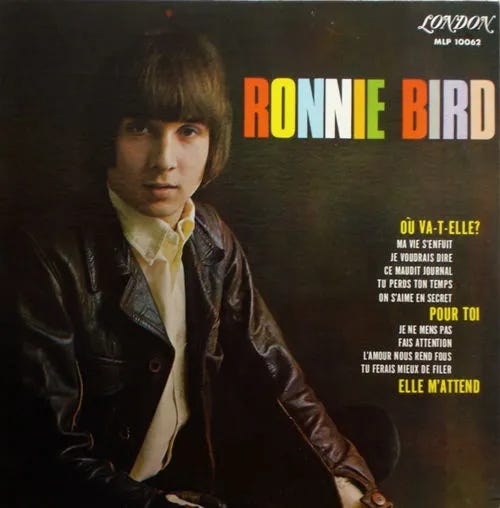

Bird’s first two releases sold something like 40,000 copies each, making considerably less money for his label than France’s bigger music names. Nonetheless, Decca continued in issuing Bird’s singles and EPs. Twelve songs from these records were collected on his first self-titled LP in ’65. A Canadian version of that album came out the following year and it was that record that I had gotten my hands on in that Montreal flea market. Almost every song on that platter kicks ass, in particular his renditions of the Pretty Things’ “Don’t Bring Me Down” (“Tu perds ton temps”), the Rolling Stones’ “The Last Time” (“Elle m’attend”), the Hollies’ “Come On Back” (“Où va-t-elle?”), the Nashville Teens’ “Find My Way Back Home” (“Fais attention!”), and the Turtles’ “Almost There” (“Ce maudit journal”). (In passing, my early-mid ‘90s garage band, Platon et les Caves, would delight in regularly blasting out our cover of “Ce maudit journal” during our gigs.)

The Ronnie Bird album offered concrete proof that the singer was very talented at mastering the rugged English r’n’b sound and so it was only fitting that he would open up for the Animals in 1965 and the Yardbirds in ’66. Ronnie’s handsome looks and debonair mod style made him a natural for photos appearing in such French teen magazines like Salut les copains and Disco Revue. But it continued to be an uphill struggle for him to sell records in massive quantities and so, in ‘66, Bird switched record labels, moving from Decca to Philips. That year saw the release of several first-rate 45s which were ultimately gathered together for a 1967 album that only came out in Canada, also entitled Ronnie Bird.

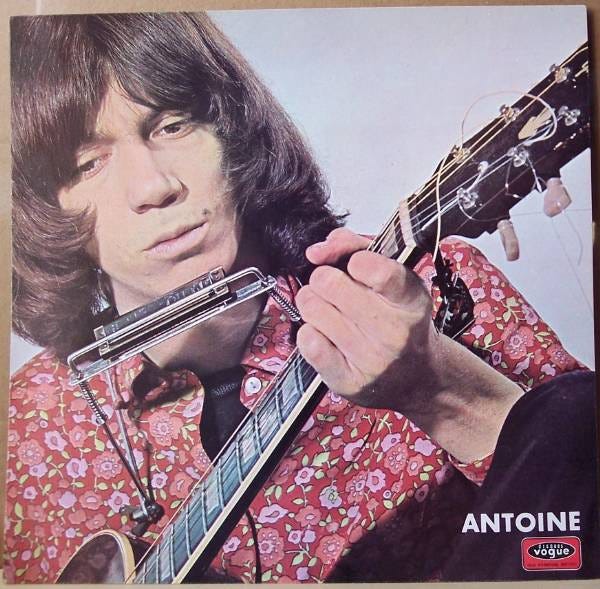

As with Bird’s earlier recordings, his 1966 material consisted largely of powerful covers including the Small Faces’ “Hey Girl”, the Knickerbockers’ “Lies” (“Cheese”), the Stones’ “Blue Turns to Grey” (“Ce n’est pas vrai”), and the Who’s “A Legal Matter” (“Ne t’en fais pas pour Ronnie”). My favorite cover, though, is that of Them’s “I Can Only Give You Everything” which Ronnie retitled “Chante”. It completely ditches the sentiments of the original version to instead address the controversy around one of the hot new stars of the French pop music scene: Antoine who came off like the country’s answer to Bob Dylan with his folk-rocking protest songs. The long-haired Antoine was labeled a beatnik and, in his tunes, humorously made fun of stars like Johnny Hallyday. With his trademark flowered shirts, he was seen by some as an opportunist with a shtick of cashing in on youthful rebellion. In “Chante”, Bird questioned Antoine’s sincerity, wondering indeed if it wasn’t basically a gimmick. This was actually just one of a good number of French songs mocking Antoine that came out at the time, a short-lived fad. Bird later admitted that the whole Antoine brouhaha was only a tempest in a teacup.

Another particularly strong offering from the album is the melancholic baroque pop ballad, “Je serre le poings”, which had also been released on an EP in early 1967. This haunting number served as a precursor for a few songs Bird would later record including his version of the Bee Gees’ “New York Mining Disaster 1941”.

The singer equally tried his hand at cutting soul-infused material such as covers of Sam and Dave’s “You Don’t Like I Know” and Edwin Starr’s “Headline News”, replete with Memphis-styled horns. American soul music was enjoying a burst of popularity in France in ’67 and Bird was only one of several musicians there to incorporate its influence in his songs. But I think he was more adept at going the orchestral and psychedelic pop route, which he did with the help of two Brits who had established themselves in France: Micky Jones and Tommy Brown.

Guitarist Jones would eventually find fame and fortune with Foreigner but that’s another story. In the early ‘60s, he and Brown were members of the English instrumental group, Nero and the Gladiators. The two moved to France where they served as session musicians for Françoise Hardy and Johnny Hallyday, among others. They also co-wrote some of the finest material Hallyday waxed including some hard rocking psych. On top of that, Jones and Brown kept busy collaborating with Ronnie Bird, beginning in mid-1966 when they helped him write my all-time favorite Bird number, “N’ecoute pas ton coeur”. It’s an outstanding example of freakbeat with some sizzling guitar work, complete with lyrics of romantic torment, Ronnie’s specialty.

Micky Jones and Tommy Brown were involved in composing several of the magnificent ditties Bird released in ’67 and ’68. “Les filles en sucre d’orge” is perhaps the finest of these, reaching what I consider to be the pinnacle of pop perfection for Bird.

Just as he had been especially gifted at capturing the sound of brash British r’n’b from 1964-66, Ronnie proved himself to be very comfortable in softer rock territory without losing a shred of credibility. In early ’68 came an EP with two standout songs. The first, “De l’autre côté du miroir” is a dreamy sensual slice of orchestral pop. The second, “S.O.S. Mesdemoiselles”, is the polar opposite: a gutsy psychedelic composition that owes a little to Hendrix’s “Purple Haze”.

1969 saw the decade’s final Ronnie Bird release, a sublime single with two moody Micky Jones/ Tommy Brown tunes, “Sad Soul” and “Rain in the City”. These are the only Sixties recordings featuring Ronnie singing in English and, alas, they marked the effective end of his career as a pop star.

Bird had had enough of hitting his head against the wall in his attempt to have hits. He was in debt, owing money to his record company and decided for a time to perform in the rock musicals Hair and Jesus Christ Superstar. Ronnie ultimately settled in New York City in 1975, working in television as a sound technician. Despite his having disappeared from view, Gallic rock lovers hadn’t forgotten his stellar musical output and he’s fortunately been well served in the last twenty years by some high-quality various artist compilations of French ‘60s pop where Ronnie Bird’s swingin’ London-styled rock/pop always has a welcome place.

I should mention that in the late Sixties, Micky Jones and Tommy Brown put out some superlative pop-psych of their own that’s well worth checking out. I’ll leave you with one shining example as well as, just for the hell of it, an insanely catchy 1966 number that deftly sums up the impact of British pop on French musicians like Ronnie Bird: Michel Sardou’s “Mods et rockers”. Vive l’Angleterre et vive la France!

Thanks Phil! Seems that so much of the best Gallic '60s has the Jones/Baker names attached. It's certainly the quality barometer for the works of Halliday and Sylvie Vartan; if J&B are involved it's gonna be hip. I know they worked with others besides Ronnie, Johnny & Sylvie. I long for a definitive report! Hard to believe what ge-ne-rock pap Jones eventually cashed in with 🤑😖