A Successful Songwriter Becomes a Troubled Troubadour

Exploring the hits and misses of P.F. Sloan

I suppose I knew P.F. Sloan’s songs well before I ever became aware of exactly who the man was. The Montreal oldies radio shows I tuned into prior to my becoming a record collector would often play splendid mid-60s Sloan-penned hits like the Turtles’ joyous “You Baby”, Johnny Rivers’ exciting “Secret Agent Man”, the Grass Roots’ angst-ridden “Things I Should’ve Said,” and Barry McGuire’s furious “Eve of Destruction”. I dug each of these songs and eventually discovered that they were all credited to the duo Sloan/Barri. Those two names appeared often on the back covers of the albums I eventually bought by the Turtles and the Grass Roots. The Sloan/Barri compositions on these LPs were all excellent. Then I found a 1965 single released by P.F. Sloan himself: “The Sins of A Family”. It was cheap; I picked it up and when I played it, I was rewarded by a harmonica-powered folk-rocker in the vein of Bob Dylan circa Bringing It All Back Home. “Perfect! I love this kinda stuff,” I thought.

From 1964 to ‘67, folkie and/or electric Dylan influenced everybody from the Beatles to the Byrds by way of Simon and Garfunkel. Song lyrics became more personal, soul-searching, literary, and occasionally surrealistic. Some vocalists would even try to imitate Dylan’s nasal declamatory singing. At times their attempts to out-Dylan Dylan could be pretty over the top and made me chuckle when I heard them. But I wasn’t giggling at these Bob wannabees, I was smiling with them because these occasionally unintentional parodies only reinforced the impact of Dylan’s singing and songwriting. Lend an ear to these numbers for a taste of rock ‘n’ roll à la Highway 61 Revisited.

As I was to ultimately discover, P.F. Sloan was possibly the best Bobby Dylan emulator of the era – though not to the point of parodying him. But his career hadn’t started that way. While Dylan was getting his feet wet in the Greenwich Village folk music circles and wowing people with his songwriting smarts, Sloan was a teenager writing tunes for hire in Los Angeles. Born Philip Gary Schlein in 1945 in New York City, his parents moved to L.A. twelve years later. Philip’s father changed his family’s last name to Sloan in light of anti-Semitic prejudice. The advent of rock ‘n’ roll hit young Philip like a ton of bricks. He auditioned for Alladin Records in 1959 and nabbed a contract with two flop singles as a result. His third 45, also released on an independent label, sank like a stone. But, fortunately, the music biz wasn’t nearly done with “Flip” (a nickname that accounts for the “F” in P.F. Sloan.)

His precocious talent for songwriting was recognized by future Dunhill Records president/chief producer Lou Adler who was working for Screen Gems in the early ‘60s. Adler eventually teamed Sloan up with tunesmith Steve Barri who was three years older than Philip. With both young men joining forces, they became a West Coast answer to New York City’s Brill Building songwriting twosomes. Sloan and Barri toiled away in their cubicle, composing tunes and recording demos in the hope of landing a hit with one of the artists cutting their songs. Finally, in March ’64, their r’n’b number for Round Robin, “Kick That Little Foot Sally Ann”, made it to a respectable #68 in the charts. The Sloan/Barri teen-pop team was on its way.

That year, Lou Adler left Screen Gems to form the Trousdale publishing company and establish Dunhill Records, taking Philip and Steve with him. The dynamic duo wrote songs recorded by actress Ann-Margret, Canadian singer Terry Black, and Jan and Dean. Black enjoyed a no. 2 smash in his homeland with the catchy “Unless You Care”. Ann-Margret’s Sloan/Barri-penned 7” single, “He’s My Man”/ “Someday Soon” may not have been a hit but nevertheless remains a killer diller two-sider. And Jan and Dean cut the fabulous theme song to the classic 1964 concert film, the “T.A.M.I. Show”, shot in Santa Monica and featuring outstanding performances by Chuck Berry, Lesley Gore, James Brown, and the Rolling Stones among other rock ‘n’ soul immortals.

P.F. Sloan and Steve Barri provided backup vocals on Jan and Dean numbers and also got the chance to try their hand at the kind of surf pop that the Beach Boys and Jan and Dean excelled at. Sloan/Barri put out 45s and an album under the name of the Fantastic Baggys on Imperial Records. If you get a kick out of the Hondells and the Rip Chords, the odds are you’d also enjoy the Sloan/Barri attempts at the vocal surf style, particularly this sizzling Fantastic Baggys cut.

It was in 1965 that Philip and Steven finally scored big as hit single songwriters for the Searchers (“Take Me for What I’m Worth”), the Turtles (“You Baby”), and Herman’s Hermits (“A Must to Avoid”). But it was with the controversial success of the most notorious protest song of all time that P.F. Sloan’s career took an unexpected turn. The tune in question is the Sloan composition, “Eve of Destruction”, released by folkie Barry McGuire. It reached the top of the charts while explicitly and indignantly enumerating the social problems faced by the U.S. at that time, be it the Vietnam War or riots in African American urban ghettos. As a result, “Eve of Destruction” was actually banned on some radio stations for being unpatriotic. If you’re already familiar with McGuire’s version, I invite you to check out the Turtles’ fine rendition from their debut LP.

What was it that inspired P.F. Sloan to pen a tune so very much unlike the numbers he had previously written? The long and the short of it is Bob Dylan. Dunhill Records head honcho Lou Adler claimed in the early ‘70s that he had stuck a Dylan album in Sloan’s hands and had told him to write material along its lines. Whether or not that’s true, Bringing It All Back Home touched more than just a nerve in Philip. It turned him on to a whole new and different approach to songwriting. The same thing happened to John Lennon, Mick Jagger, and Pete Townshend, among many others. But “Eve of Destruction” was blatant in its attempt to wed the style of Dylan’s ’63 period “finger-pointing” songs with the new sound of folk-rock, and long-time folkies denounced the smash single as cheap exploitation. What they didn’t know was that Sloan was completely sincere walking his boot heels along this new socially conscious and introspective songwriting path.

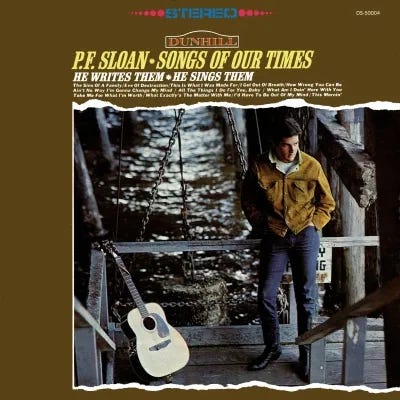

Thanks to the success of “Eve of Destruction”, Philip was rewarded with the opportunity to release his first solo Dunhill 45 in August 1965 and an album the following month. The 7”, “The Sins of a Family” described the sad life of a teenaged girl who grew up in a toxic household. This powerful song, produced by Steve Barri, wasn’t a hit nor was the LP, Songs of Our Times. And what a pity that was as the album contains a dozen strong tracks, some credited solely to Sloan, others to the Sloan/Barri team. The sound of the LP is pretty sparse and showcases Philip on guitar and harmonica. He offers up his own versions of “Take Me for What I’m Worth” and “Eve of Destruction”, but “I Get Out of Breath” and “What Am I Doing Here with You” are two more of the LP’s several highlights.

Songs of Our Times is the perfect distillation of adolescent angst, appropriately enough when you consider that its contents were written by a nineteen-year-old. Sloan’s lyrics may lack the sophistication of his role model Dylan but are absolutely sincere and take on greater force with Philip’s expressive singing. Even if Songs of Our Times didn’t blaze up the charts, Dunhill provided Sloan with another chance to record an album, once again produced by his songwriting partner.

Twelve More Times came out in February ’66 and improved upon Flip’s previous LP, especially because of its fuller sound courtesy of the top-notch Wrecking Crew musicians like drummer Hal Blaine and bassist Joe Osborn. The quality of Sloan’s songs was generally higher than on his first album, and when it comes to passionately conveying what the post-teenage blues feel like, Twelve More Times is a folk-rock record that ranks right up there with Simon and Garfunkel’s Sounds of Silence, released that same year. I especially love the romantic “I Found a Girl” and the Dylan-esque “Halloween Mary”.

Despite its strengths, Twelve More Times met the same commercial fate as its predecessor and didn’t sell well. No matter how hard Sloan tried, the material he released under his name just couldn’t strike gold the way his compositions for the Turtles or Johnny Rivers did. This must’ve been incredibly frustrating for this West Coast pop wunderkind. Dunhill ultimately put out three last 45s before cutting him loose. Alas, none of these were hits, but, for my money, Sloan’s final Dunhill single from October ’67 contains two of his best tunes. “I Can’t Help But Wonder, Elizabeth” is a gorgeous melancholic love song while “Karma (A Study in Divinations)” lives up to its title by being a psychedelicized paean to spiritual consciousness.

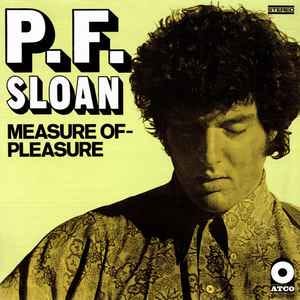

The world had to wait until 1968 for the release of a third P.F. Sloan album, this time on the ATCO label. Measure of - Pleasure was its title and it was produced by the legendary Tom Dowd who had helmed recordings by Wilson Pickett, Dusty Springfield, and Aretha Franklin. Measure of - Pleasure had a more mature soul-inspired quality with Sloan no longer coming off like the callow anxious folk rocker of his mid-60s efforts. (Although I do prefer him as a rockin’ folkie.) Even if it was a solid piece of work, the album’s failure in the marketplace resulted in Sloan withdrawing from the music world for decades, barring a 1972 LP that also went nowhere. He did release an album in 2006 as well as in 2014 but passed away from pancreatic cancer the following year. Sloan was seventy years old.

But that’s not quite where my P.F. Sloan story ends, actually. For I’d be remiss in not bringing up his instrumental role in the creation of the Los Angeles group, the Grass Roots. They were actually the invention of Lou Adler and the Sloan/Barri duo who released an album in 1966 under that band name: a mixture of decent covers by the Rolling Stones, the Lovin’ Spoonful, and Simon and Garfunkel as well as strong originals like the Rubber Soul-influenced “I’ve No More to Say”. The terrific teenbeat single “You’re a Lonely Girl” preceded the album and is my favorite of Sloan’s Grass Roots’ recordings.

To make a pretty long story short, Sloan and Barri were too busy to continue with their Grass Roots project. Eventually, an L.A. combo called the 13th Floor filled their shoes and became the Grass Roots. They had a top 10 hit in ’67 with “Let’s Live for Today” and, before they became a lightweight pop rock outfit, put out two first-rate albums which included several nifty Sloan/Barri-penned numbers.

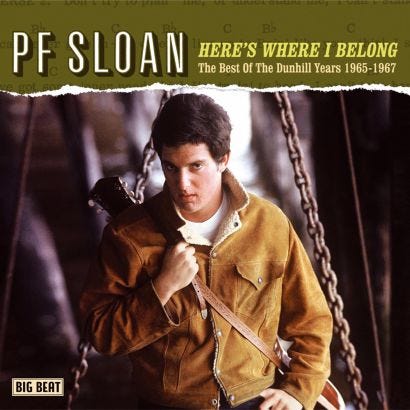

It's a cryin’ shame that P.F. Sloan didn’t achieve more recognition for his solo output in the mid-Sixties. As far as I’m concerned, the quality of his material approaches that of folk-rock troubadours like Fred Neil, Phil Ochs, and Tim Hardin, and the fact that he was rooted in rock ‘n’ roll as opposed to the folk revival actually gives his songs an extra pop power. But then, almost every singer/songwriter other than Dylan, Donovan, and Paul Simon struggled to find a mass audience at the time and I’m glad that many of them, including P.F. Sloan, have finally gotten their due with numerous reissues. To hear much more of Sloan’s sterling ‘60s folk rock, I suggest the 2008 Ace Records CD collection, Here’s Where I Belong – The Best of the Dunhill Years 1965-67. Delving into that disc would be a great way to take him for what he’s worth, to paraphrase the title of one of Philip “Flip” Sloan’s outstanding songs.

Those are some great music clips especially the Dick Campbell and the other two that channel Dylan. When you said Dylan imitators I was thinking of the first David Blue record. But he grew out of it. Anyway as soon as I saw this was about PF Sloan I figured you'd start off with "Where were you when I needed you" by The Grass Roots which was one of the first 45's I bought. I seem to remember that the first version of the song had Sloan himself, or maybe Barri singing. Anyway I have had all the Sloan records you posted but I think I only have Twelve More Times at this moment. This was really fun to read.